![Kim Tae Hyun, chair of the physician workforce supply-and-demand projection committee, briefs reporters on the panel’s 12th meeting results at the Government Complex Seoul in Jongno District, Seoul, on Monday. [Photo by Yonhap]](https://image.ajunews.com/content/image/2025/12/30/20251230204557184503.jpg) Kim Tae Hyun, chair of the physician workforce supply-and-demand projection committee, briefs reporters on the panel’s 12th meeting results at the Government Complex Seoul in Jongno District, Seoul, on Dec. 29, 2025. [Photo by Yonhap]SEOUL, December 31 (AJP) -South Korea could face a shortage of up to about 11,000 doctors by 2040, according to a new government-backed projection, underscoring brewing healthcare crisis rooted in delayed medical reform after a year-long fallout from mass walkouts by doctors.

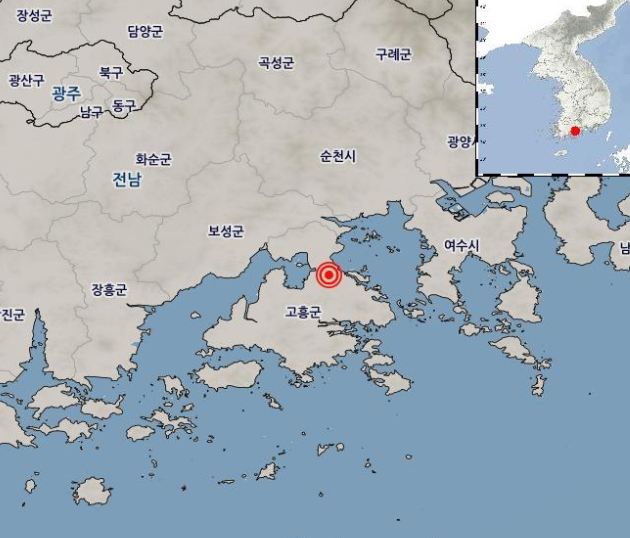

Kim Tae Hyun, chair of the physician workforce supply-and-demand projection committee, briefs reporters on the panel’s 12th meeting results at the Government Complex Seoul in Jongno District, Seoul, on Dec. 29, 2025. [Photo by Yonhap]SEOUL, December 31 (AJP) -South Korea could face a shortage of up to about 11,000 doctors by 2040, according to a new government-backed projection, underscoring brewing healthcare crisis rooted in delayed medical reform after a year-long fallout from mass walkouts by doctors. The estimate was released Tuesday by the physician workforce supply-and-demand projection committee, an independent body under the Ministry of Health and Welfare. The panel projected that physician demand will continue to outpace supply even under multiple scenarios that factor in productivity gains from artificial intelligence and policy efforts to curb excessive medical use.

Under its baseline model, the committee forecast demand of 144,688 to 149,273 doctors by 2040, compared with a projected supply of 138,137 to 138,984 — leaving a shortfall of 5,700 to 11,100 physicians. In 2035, the gap is estimated at 1,500 to 4,900 doctors.

The findings will be submitted to the Health and Medical Policy Deliberation Committee, which is preparing to review medical school enrollment quotas for the 2027 academic year and beyond. Intensive discussions are expected to begin in January.

The projection revives a politically sensitive issue that triggered one of the most serious healthcare disruptions in recent years. In February 2024, the government announced plans to raise annual medical school admissions by 2,000 students — a 67 percent increase — beginning in 2025, citing long-term shortages linked to population aging. The move prompted strong opposition from doctors’ groups, leading to mass resignations by residents and interns. At the peak of the protest in March 2024, more than 11,000 doctors had left their posts, forcing hospitals to scale back surgeries and emergency services.

Student strike protesting to enrollment quota increase in Yeoui-do, Seoul in August, 2020 (Yonhap)

Student strike protesting to enrollment quota increase in Yeoui-do, Seoul in August, 2020 (Yonhap)Beyond overall headcount, the data point to deep imbalances in how medical labor is distributed. An increasing number of newly licensed doctors are opening private clinics in highly profitable, low-risk fields such as dermatology and plastic surgery, while essential specialties continue to face shortages.

From January to July 2025, 176 new clinics were opened by general practitioners, up 36.4 percent from a year earlier. Dermatology accounted for more than 80 percent of those openings. By contrast, the number of pediatric specialists declined to 6,438 in July 2025, down from the previous year.

Regional disparities remain pronounced. About 70 percent of new clinics are concentrated in the Seoul metropolitan area, leaving many rural regions struggling to secure emergency, obstetric and surgical services.

Health officials acknowledge that expanding medical school enrollment alone cannot resolve these imbalances. High litigation risks, long working hours and relatively low compensation continue to deter young doctors from entering essential fields.

The government has pledged to invest 10 trillion won by 2028 to raise fees for critical specialties, but experts say financial incentives alone are unlikely to be sufficient without broader reforms to training, liability rules and regional deployment.

As deliberations resume over future enrollment quotas, the new forecast highlights why physician supply remains one of the country’s most politically sensitive policy challenges — a problem temporarily contained but far from resolved.

Medical school enrollment quotas are politically sensitive in Korea because they sit at the crossroads of healthcare policy and elite education.

Expanding quotas affects not only the long-term supply of doctors but also the country’s highly competitive university hierarchy, as top-performing students overwhelmingly prefer medical schools for their income stability and social status. Any change reshapes entrance exam dynamics, private education demand and the allocation of elite talent away from science and engineering.

Choe In-hyeok 기자 inhyeok31@ajunews.com

![[포토] 폭설에 밤 늦게까지 도로 마비](https://image.ajunews.com/content/image/2025/12/05/20251205000920610800.jpg)

![[포토] 예지원, 전통과 현대가 공존한 화보 공개](https://image.ajunews.com/content/image/2025/10/09/20251009182431778689.jpg)

![블랙핑크 제니, 매력이 넘쳐! [포토]](https://file.sportsseoul.com/news/cms/2025/09/05/news-p.v1.20250905.c5a971a36b494f9fb24aea8cccf6816f_P1.jpg)

![[포토]두산 안재석, 관중석 들썩이게 한 끝내기 2루타](https://file.sportsseoul.com/news/cms/2025/08/28/news-p.v1.20250828.1a1c4d0be7434f6b80434dced03368c0_P1.jpg)

![[작아진 호랑이③] 9위 추락 시 KBO 최초…승리의 여신 떠난 자리, KIA를 덮친 '우승 징크스'](http://www.sportsworldi.com/content/image/2025/09/04/20250904518238.jpg)

![블랙핑크 제니, 최강매력! [포토]](https://file.sportsseoul.com/news/cms/2025/09/05/news-p.v1.20250905.ed1b2684d2d64e359332640e38dac841_P1.jpg)

![[포토] 국회 예결위 참석하는 김민석 총리](https://cphoto.asiae.co.kr/listimg_link.php?idx=2&no=2025110710410898931_1762479667.jpg)

![[포토] 박지현 '아름다운 미모'](http://www.segye.com/content/image/2025/11/19/20251119519369.jpg)

![[포토] 키스오브라이프 하늘 '완벽한 미모'](http://www.segye.com/content/image/2025/09/05/20250905504457.jpg)

![[포토]첫 타석부터 안타 치는 LG 문성주](https://file.sportsseoul.com/news/cms/2025/09/02/news-p.v1.20250902.8962276ed11c468c90062ee85072fa38_P1.jpg)

![[포토] 김고은 '단발 여신'](http://www.segye.com/content/image/2025/09/05/20250905507236.jpg)

![[포토] 박지현 '순백의 여신'](http://www.segye.com/content/image/2025/09/05/20250905507414.jpg)

![[포토] 알리익스프레스, 광군제 앞두고 팝업스토어 오픈](https://cphoto.asiae.co.kr/listimg_link.php?idx=2&no=2025110714160199219_1762492560.jpg)

![[포토] 발표하는 김정수 삼양식품 부회장](https://image.ajunews.com/content/image/2025/11/03/20251103114206916880.jpg)

![[포토] '삼양1963 런칭 쇼케이스'](https://image.ajunews.com/content/image/2025/11/03/20251103114008977281.jpg)

![[포토] 아이들 소연 '매력적인 눈빛'](http://www.segye.com/content/image/2025/09/12/20250912508492.jpg)

![[포토] 한샘, '플래그십 부산센텀' 리뉴얼 오픈](https://image.ajunews.com/content/image/2025/10/31/20251031142544910604.jpg)

![[포토]끝내기 안타의 기쁨을 만끽하는 두산 안재석](https://file.sportsseoul.com/news/cms/2025/08/28/news-p.v1.20250828.0df70b9fa54d4610990f1b34c08c6a63_P1.jpg)

![[포토] 언론 현업단체, "시민피해구제 확대 찬성, 권력감시 약화 반대"](https://image.ajunews.com/content/image/2025/09/05/20250905123135571578.jpg)

![[포토]두산 안재석, 연장 승부를 끝내는 2루타](https://file.sportsseoul.com/news/cms/2025/08/28/news-p.v1.20250828.b12bc405ed464d9db2c3d324c2491a1d_P1.jpg)

![[포토] 김고은 '상연 생각에 눈물이 흘러'](http://www.segye.com/content/image/2025/09/05/20250905507613.jpg)

![[포토] 키스오브라이프 쥴리 '단발 여신'](http://www.segye.com/content/image/2025/09/05/20250905504358.jpg)

![[포토] 아홉 '신나는 컴백 무대'](http://www.segye.com/content/image/2025/11/04/20251104514134.jpg)